*****IF YOU WISH TO ORDER HARD COPIES OF OUR BOOKS, PLEASE VISIT https://livingjusticepress.org*****

In this book Waziyatawin, Dakota, explores how we can embark on a path to respectful coexistence with the Original Peoples of Minnesota who have suffered from policies of genocide. A widely used textbook in both high school, church, and college classes, What Does Justice Look Like? offers ways to "put things right" with the Original People of the land.

During the past 150 years, the majority of Minnesotans have not acknowledged the immense and ongoing harms suffered by the Dakota People ever since their homelands were invaded over 200 years ago. Many Dakota people say that the wounds incurred have never healed, and it is clear that the injustices—genocide, ethnic cleansing, mass executions, death marches, broken treaties, and land theft—have not been “made right.” The Dakota People paid and continue to pay the ultimate price for Minnesota’s statehood. This book explores how we can embark on a path of transformation on the way to respectful coexistence with those whose ancestral homeland this is. Doing justice is central to this process. Without justice, many Dakota say, healing and transformation on both sides cannot occur, and good, authentic relations cannot develop between our Peoples. Written by Wahpetunwan Dakota scholar and activist Waziyatawin of Pezihutazizi Otunwe, What Does Justice Look Like? offers an opportunity now and for future generations to learn the long-untold history and what it has meant for the Dakota People. On that basis, the book offers the further opportunity to explore what we can do between us as Peoples to reverse the patterns of genocide and oppression and instead to do justice with a depth of good faith, commitment, and action that would be genuinely new for Native and non-Native relations.

Praise for What Does Justice Look Like?

Choice: Current Reviews for Academic Libraries

August 2009, Vol. 46, No. 11

Reviewed byF. E. Knowles, Valdosta State University

In this important work, Waziyatawin (indigenous governance, Univ. of Victoria, BC) develops the history of the Dakota Indians in Minnesota. She reveals through summaries of Sioux [sic] interaction with the Ojibwa and then white settlers that what Americans know as Minnesota has always been the homeland of the Dakota. Further, the historic accounts of the interaction between Native Americans and white colonizers have necessarily been told in the voice of the colonizer. There is another half to history. The author discusses the origin accounts that are inherent in the Dakota culture that, as is the case with many if not most Indian people, are at odds with the conventional wisdom held by Western academia. While Waziyatawin’s use of origin and history to establish the Dakota in what is now Minnesota is fascinating, it is merely a foundation for the gist of the book—the impact of first contact with whites and the continuing effects of colonization. Waziyatawin makes a convincing case that the devastation of colonization continues through public policy and the hegemonic construction of public opinion. In that sense, the book’s impact can be felt in the daily lives of many Native Americans today.

Summing Up: Highly recommended. All levels/libraries.

The Circle News: News from a Native American Perspective, January 2009

Louise Erdich, Anishinabe author

A passionate and unyielding voice for justice, Waziyatawin, Dr. Angela Wilson, advocates for Minnesota Truth vs. Minnesota Nice. This book is first of all a terse and eloquent recapitulation of Minnesota history in relation to the Dakota, in other words, it is a clear eyed and sorrowful account of genocide. Waziyatawin uses the loaded word genocide with a careful explanation of its accuracy. She is painstaking in her efforts to bring clarity to a divisive subject.

It is so important for Indigenous people in Minnesota, whatever their tribal origins, to stand together. For that reason, I hope that Waziyatawin’s ideas can be separated from any personal issues with other tribal people—some of which are recounted in this book. Considering our mutual history, we should all rise above the small, the petty, the all-too-human ways that tribal people are forced to struggle with each other for recognition by the power brokers in a dominant culture. Waziyatawin’s forceful recommendations for reparation, if adopted, could make Minnesota a leader in the difficult task of integrating the ugly truths of our history into an understanding of this state’s, and this country’s, relationship with Indigenous People.

Acknowledging the truth makes a people stronger, not weaker. As a specific example, Waziyatawin compares Fort Snelling’s disgraceful “fun fort” self-depiction with the somber reality that imbues other concentration camps and Holocaust memorials. The compelling facts about Fort Snelling include the sacred nature of the land itself, and the fact that it is filled with the marked and unmarked graves of Dakota ancestors, including women who starved themselves to death out of grief, women raped by soldiers, children and elders dead of sicknesses that raged through the fort. Minnesotans also hanged Dakota leaders on that earth. And so when Waziyatawin quite reasonably advocates returning the Fort to the Dakota to do with as they decide, it would seem an act of unquestionable justice. It seems, in fact, a great idea.

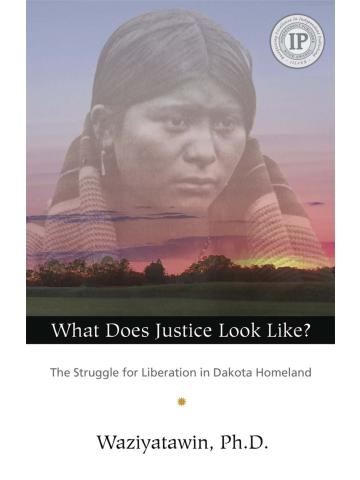

Nobody who reads this book will ever drive to the airport again without seeing the devastated woman on the cover—a young woman interned in what became a death camp in the winter of 1862–63. If Fort Snelling were to become a Dakota garden and ceremonial ground, the young woman’s thousand-mile stare would at last rest with the living.

The Wicazo Sa Review

Elizabeth Cook-Lynn, Dakota/Sissetowan; Crow Creek Sioux Tribe

Author of Anti-Indianism, A Separate Country, New Indians, Old Wars

Perhaps the most important question posed in this regional text about the development of the state of Minnesota is this: "What does recognition of genocide demand?" (p. 75) The question is asked because, as the writer documents, most U. S. and regional historians are loathe to write and speak of the word….

"The Minnesota Historical Society continues to resist using appropriate and accurate terminology such as "genocide" and "ethnic cleansing" and "concentration camp", preferring instead more benign terms that diminish the horror of Minnesota history. This is not a reflection of ignorance, since the Minnesota History Society houses a lot of evidence within its archives.

It is a deliberate historiography, this writer asserts, perpetrated by one of the significant academic institutions in the region. Furthermore, she says, this Society, founded as it was by former state governor Alexander Ramsey, is steadfastly upholding its corrupt legacy of democratic ideals cloaked in generations of racist and colonial policy toward the Dakotahs, the indigenous peoples of the region. And it does so almost without critical assessment from other historical establishments. The question asked here in this significant historical work could be asked of Indigenous policy across the entire country, which was initiated when President Thomas Jefferson in 1807 advocated extermination of the tribes by declaring:

"If we are to be constrained to lift the hatchet against any tribe, we will not lay it down until that tribe is exterminated…" and again in 1813 when he wrote "The American Government has no other choice before it than to pursue [the Indians] to extermination."

This is a text that should replace the histories that are used in the schools in this region. What Waziyatawin points out is that the unnecessary and immoral policy of the Federal government of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries quickly became state policy throughout the land. And it continues today, and it can be challenged. To make that point, she suggests that the nation of America might have been developed otherwise, were it not for greed, avarice, racism, the acceptance of brutal capitalistic colonial interests, and the coveting of lands belonging to others. That may not be a comforting thought for those who have been taught to love a fantasy history about America, but it does give a blueprint for a more just future. …

American Indian Culture and Research Journal 34:1 (2010) 183-186

Reviewed byJeff Means, University of Wyoming

Author Waziyatawin offers a powerful visiion for future Dakota-US relations in What Does Justice Look Like? The Struggle for Liberation in Dakota Homeland. This book makes a significant leap forward from previous studies pertaining to Native American decolonization by providing the foundational blueprint necessary for true cultural understanding, respect, and empathy between Native and Anglo-American societies.

The core of her thesis is a call for justice for the Dakota tribe of Minnesota after centuries of cultural oppression. Ultimately, she argues that justice will only be achieved by the restoration of the Dakota homeland and monetary reparations. However, the author understands that for this goal to come to fruition a paradigm shift in American cultural consciousness must occur in regard to Anglo-American perceptions of both their own past actions toward the Dakota and how these past transgressions must be ameliorated. She creates her blueprint by synthesizing and building upon previous ideological theories and political actions in Indian country in order to provide a forward-thinking delineation of the cultural and logistical changes needed to bring justice and cultural balance to the relationship between Native Americans and the United States. …

The author immediately sets a straightforward tone concerning her belief in the necessity of land restoration and monetary reparations by placing the responsibility for past and current colonial exploitations and hegemonic controls squarely on the Anglo-American Minnesota residents. She calls for an end to continued colonial threats to Dakota culture and notes that, "we must all rethink our ways of being and interacting this this world to create a sustainable, healthy, and peaceful co-existence with one another and with the natural world" (13). In order to help Anglo-Americans achieve this understanding, the author provides a historical glance at Dakota-white relations. She quite correctly uses the Dakota origin story to demonstrate the tribe's clear ties and aboriginal claims to the land the Dakota called Minisota. …

Her most powerful and pertinent examples of the outrages committed against the Dakota at the hands of Anglo-Americans focus on the white invasion of Minnesota and the "legalized land theft" that occurred through treaties that white Minnesotans universally failed to honor. Most notable, the author argues that white Minnesotans committed genocide against the Dakota by using the United Nations agreed-upon standards of deciding what constitutes genocide. She demonstrated clearly that Anglo citizens of Minnesota committed all five of the acts of genocide upon the Dakota. The most powerful example of this occurred after the Dakota were defeated in the war of 1862. After having to endure forced marches, the Dakota were separated by gender and imprisoned in Fort Snelling during the winter of 1862. In the spring of 1863 the Dakota people were forcibly removed from the state of Minnesota because Anglo citizens called for either their extermination or removal.

Having provided a foundation understanding of the historical treatment the Dakota endured, the author examines the measures needed to address fairly these previous injustices and the obstacles they face. It is here that the book gains momentum. Waziyatawin adds considerable depth to her study by displaying a clear and complex understanding of the obstacles and challenges the tribe faces as it seeks to achieve these goals. Education of Anglo-American Minnesotans about their harsh treatment of the Dakota people, past and present, is a necessary first step. However, the Native perspective of Minnesota's history is not available in its public schools. In order to overcome this difficulty the author turns to her book For Indigenous Eyes Only: A Decolonization Handbook (2005) by calling for community truth-telling activities that would enlighten white communities as to past Dakota suffering and act as a cathartic process through which the Dakota may begin to heal their historical trauma. Only then will both peoples be able to provide a level of justice for the Dakota. …

Waziyatawin has produced a well-written and thoughtful book that sets the tone and level of discussion where it needs to be to achieve final justice in Indian country. It is also fitting that his book emphasizes education because it should be assigned to any and all high school and college classes that pertain to Native American studies. Reading and discussing this book can be the first step in creating the new social order Waziyatawin seeks. Unfortunately, the fruition of these Native aspirations may take decades, if not centuries, to be realized. African Americans still struggle to attain their cultural goals in America; it will be a longer process for Native Americans.

Anson Black Calf Wanblii Ake Glii, Lakota

The book 'What Does Justice Look Like?: The Struggle for Liberation in Dakota Homeland' has been one of the best books I've ever read! I couldn't put it down, I had to finish it as fast as I could, and I did in a matter of days!

Written primarily in response to Minnesota's celebration of it being a state for 150 years in 2008, and its Sesquicentennial Commission asking its citizens to reflect back on what they've gained and how much they've progressed as a state since, Waziyatawin, Ph.D., does exactly that, but from a Dakota perspective. And rather than looking at the past 150 years from a Euro-American point of view of "celebration" and in terms of "gain" and "progress." She looks at it from an Indigenous outlook and measures how much the Dakota people lost and had stolen from them instead.

Waziyatawin, a noted Dakota scholar and activist, relates the history of her People before European arrival,and the often violent and traumatic history since that time.

Taking the reader through a crash course of Dakota-American history, Waziyatawin briefly, but accurately gives direct examples of the unjust crimes of humanity that were committed against the Dakota people by the early Euro-Americans.

And through these historic examples, she not only explains how Euro-American actions ultimately stole Dakota lands and lives, but that the effects of these crimes are still in continuation today, and to a large extent, continually ignored and supported by the US power structure of government.

Waziyatawin speaks undeniable truths about our concealed history and brings to light the most important historical and continuing contemporary injustices against the Dakota people.

As well as giving very clear suggestions for what American people could begin doing to support Indigenous people in our struggle for restorative justice and liberation.

She stresses the need for Lakota and Dakota people to remember the Oceti Sakowin (the original seven counsel fires) and traditional ways of our people in our beginning to work toward justice and liberation.

In reading this book it gave me more of an insight about the history of our entire Sioux people in learning specifically what our eastern Dakota relatives—our people—first experienced in their early dealings with the Euro- Americans, and what they currently face as a people largely living in exile today!

It is an essential read for anyone who considers themselves Lakota or Dakota, and it is also a wake up call to the entire state of Minnesota, as well as all of the United States. With its message being that this country is not as free, equal, and just as some may think.

For it is in fact completely the opposite when the history of this entire nation is looked at from the Indigenous perspective. But this call is not just for a state and national awareness to begin, it is also a call to the US government that they need to take responsibility for the restitution they owe Indigenous people.

Long has our voices for justice and liberation been ignored and silenced.

It is definitely time for an era of truth telling, land restoration, and restorative justice to begin! And this is exactly what this book is about.

Minnesota Reads, March 30, 2009

Reviewed by Ben Kimball

Waziyatawin's 2008 book What Does Justice Look Like? is a book about the struggle of the Dakota people to achieve liberation in Minnesota. Waziyatawin used the occasion of Minnesota's Sesquicentennial to illustrate the need to both recognize the genocide and oppression of the Dakota and to install a policy of reparative justice that would both return land (areas formerly Dakota and now public) and allow the Dakota the freedom to live as they so choose on that land.

In this book, Waziyatawin built a moral case for reparative justice. First, Waziyatawin gave us a well-researched and cited history of how both the United States and eventually the State of Minnesota took land and committed genocide against the Dakota. To begin to right the wrongs, Waziyatawin advocated for a culture of truth telling by both the Dakota and non-indigenous Minnesotans about what really happened when Europeans settled the area that became Minnesota. Waziyatawin then showed the necessity for the removal of Fort Snelling, a symbol of colonization that once was a Dakota concentration camp and a site where Dakota people were publically executed. Not stopping there, Waziyatawin moved forward in this vision and showed both the benefits of Dakota liberation and how all people can live in peaceful coexistence.

I can certainly see how many non-indigenous Minnesotans may feel offended and shocked by what is written in this book. Waziyatawin exposed many disturbing historical details about the Dakota genocide. This history is not often discussed in most elementary schools and museums. What may be more shocking for many are the ideas Waziyatawin has for making things right. Many people cling to their worldviews so tightly that when challenged with reality, they become hostile. Waziyatawin gave several examples of this very idea by showing letters to the editor printed in the Star Tribune.

However, when one is presented with the evidence and reality, the path to reparative justice becomes clear and necessary. I personally agree with Waziyatawin's conclusions in this book….